The Space Time Conundrum in Water Polo

A comparison of water polo to other time constituted sports

One of my favorite stories in all of sports history is that of the invention of the NBA shot clock. For the full story check out the linked article below, but I’ll summarize for those unfamiliar. In the early days of professional basketball, the league had a serious problem: teams were often adopting stalling tactics in order to maintain leads and possession. Well it may have been a reasonable strategy towards the goal of winning a game, spectators were understandably less than thrilled to watch one team play keep-away for long stretches of time and result in boring, low-scoring affairs. Enter Syracuse Nationals owner Danny Biasone and general manager Leo Ferris. After doing some back of the napkin math using box scores from games where stalling wasn’t employed, they determined that the best games had each team taking about 60 shots. When that number was divided by the 48 minute game time, the 24 second shot clock was born. The league soon adopted the 24 second clock as the standard and other basketball leagues soon followed suit with shot clocks of varying times. Likewise, other sports where stalling was a possibility or pace of play could be improved also adopted similar possession clocks to speed up play and keep the game exciting; among these sports was water polo.

Broadly defined, these sports–and any that have a time limiting the span of the contest–fall within the categorization of time constituted sports. However, additional time constraints placed on players like a shot clock or the five second rule in basketball further the relationship of the players with time by regulating their play in addition to constituting it. In so doing, these time constraints serve to influence positive play as well as adding additional pressures on athletes and serve as part of the human challenge of the sport represented in the rules of the game.

However, the story of the basketball shot clock (apocryphal or not) interests me for another reason: the clock was conceived and instituted because of the spectator experience of the game. Regardless of how players or coaches may have felt about it, the advent of the shot clock not only acknowledged but prioritized the sport of basketball as an entertainment product. Furthermore, the shot clock prioritized the aesthetic of the game, how it appeared when presented to an audience, over any notions of playing winning basketball. Sports and sports coaching are a naturally conservative and zero-sum endeavor where the result (winning) often takes precedence over the method used to achieve it. Without the pressure of the spectator experience and the financial incentives it created driving the change in basketball, it is not impossible to envision basketball never adopting the shot clock at all and subsequently not having the international reach it currently does.

Unlike basketball, the history of the shot clock in water polo does not have a fun story attached to it, nor does it have the back of the napkin math as a rationalization. In fact, the adoption of the shot clock in water polo is much more sporadic. The shot clock was first introduced in water polo in 1971 at 45 seconds, amended to 35 in 1977 and then finally to 30 seconds in 2005. Notable about this adoption is that at its inception the game was limited to four 5-minute quarters. 7-minute quarters were adopted in 1981 and the current 8-minute periods weren’t adopted until 2005 (concurrently with the adoption of the 30 second shot clock). So, even if there was once a rationalization similar to that used in basketball, the game clock has changed so much since then that it is largely irrelevant. I can imagine the rule makers in 2005 being rather pleased with the round 30 second number and how evenly it divided the new 8 minute periods, but this is speculation of course. Regardless, the reasoning for the shot clock in water polo mirrored the desire to speed up the pace of play as in other sports.

Well I agree with the desire to have a fast-paced and exciting game both from an aesthetic and spectator perspective, I believe that there is an important factor that is missing in the thinking about the shot clock for water polo as it compares to other sports. That factor is the medium in which the sport is played; water is harder to move through than air. Water polo is one of the most unique sports in the world because it is the only team ball sport not played on a court or field but instead in the water; it is imperative that this difference in the medium of the game be considered when thinking about the logic of the shot clock in water polo. So, in the spirit of Biasone and Ferris, let’s do some back of the napkin math in order to examine the shot clock in water polo and see how it compares to other sports.

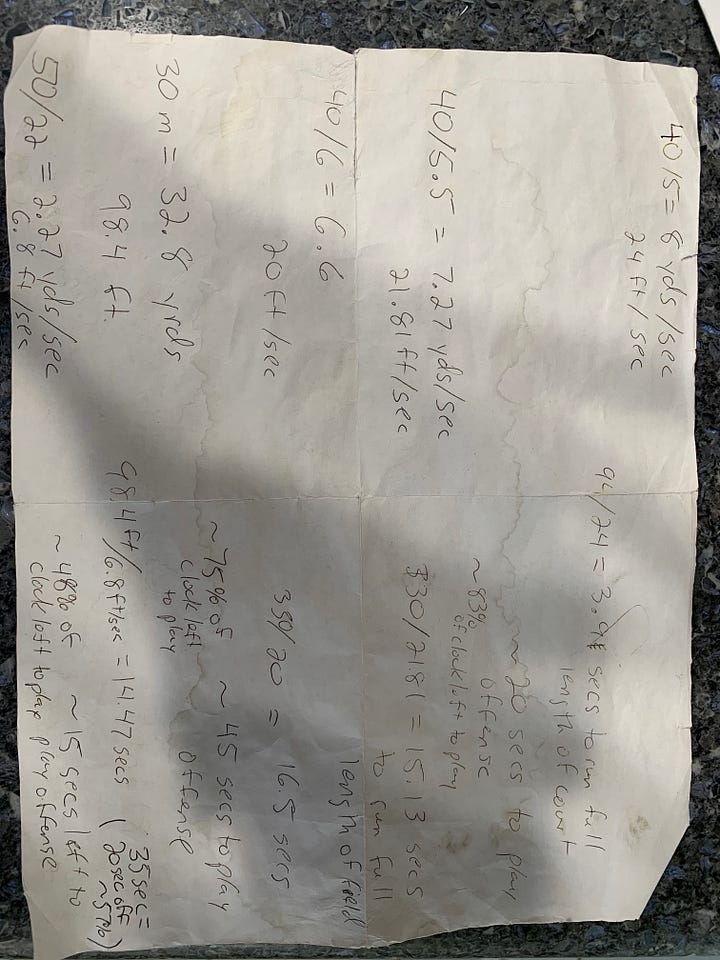

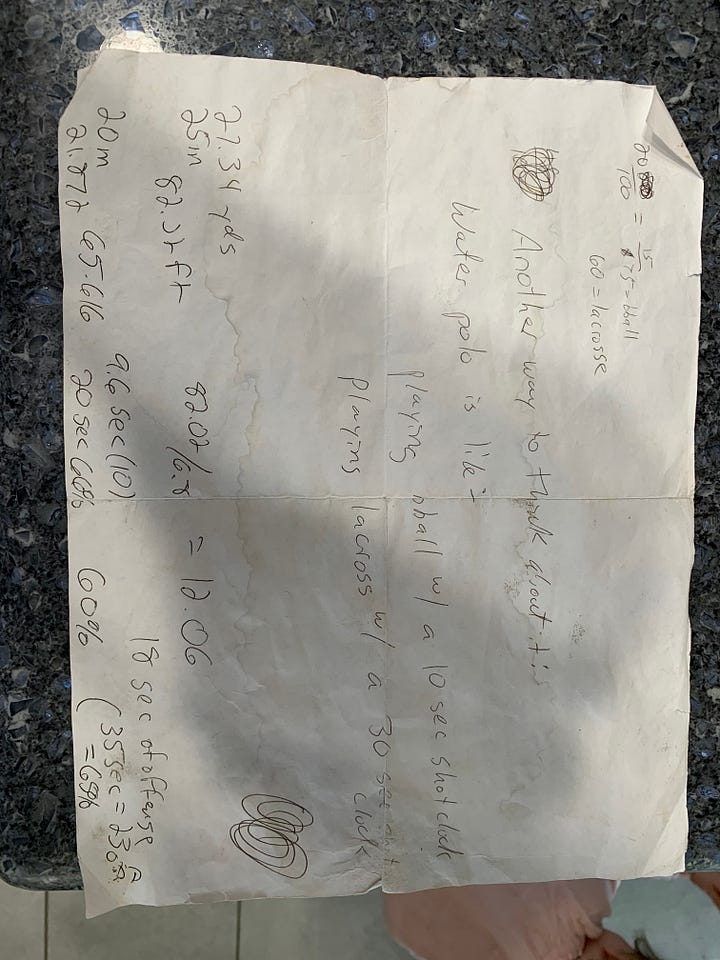

Since we began this discussion with basketball, it is illustrative to start there. As noted, the shot clock in basketball is 24 seconds long. Adding the dimension of space, the NBA standardizes the court at 94 feet. The NBA undoubtedly employs some of the greatest athletes in the world, so let’s assume that most players in the NBA could do a 40 yard dash in a fairly decent time of 5-5.5 seconds. That player, at a sprint, is moving 21-24 feet per second which means that they could run the full distance of the court—baseline to baseline—in something like 4-4.5 seconds. Considering the 24 second shot clock (as well as the rules regarding getting the ball across the centerline) that means that there are often 20 or more seconds in which an NBA team can play offense. That 20 seconds is a full 80+% of the time allotted by the shot clock in which to run various offensive sets. Granted, every player may not be sprinting down the floor at every possession, but nor is every player running all the way from baseline to baseline on every possession. Therefore, for the purposes of this discussion it serves to illustrate the relationship between the athlete, the shot clock and the playing surface.

Looking at another sport that uses a shot clock to manage the pace of play, the sport of college lacrosse utilizes an 80 second shot clock (the ball must be cleared within 20 seconds much like the 5 second rule in basketball) with a field of play that is 110 yards long. With no offense intended to college lacrosse players, let’s assume they are slightly slower than an NBA player; say they average a 40 yard dash of 5.5-6 seconds. Using the same methodology as above, a player at a full sprint covers roughly 20-22 feet per second and can run end-to-end on a lacrosse field in 15-16.5 seconds. It is again acknowledged that players are not always running full speed, but also that they aren’t often running from one end line to the other either. However, using this number as a rough guide leaves 60-63.5 seconds in which a lacrosse team can run their offense (incidentally, the reset of the clock on a shot in which the attacking team maintains possession resets to 60 seconds, so that reinforces this number as a reasonable amount of time for a team already in the offensive end to construct an attack). Therefore, in lacrosse a team still has 75+% of the shot clock remaining after they have transitioned from defense to offense.

Water polo is played on a 30 meter course with a shot clock of 30 seconds; however, unlike the two sports above the athletes aren’t running but instead moving through the water. This difference in playing medium greatly influences the speed at which an athlete can transverse the field of play. Assuming a 50 yard freestyle time of 22 seconds—a time Ryder Dodd, who is one of the faster members on the USMNT, has swam in a meet before—that means a water polo athlete is moving 6-7 feet per second (which may be more than generous considering I am not bothering to account for the dive or turn). This speed means a water polo player can possibly get from one end line to the other in about 15 seconds. Those familiar with water polo will recognize that 15 seconds is a common timeframe for a team to get down the pool and into their offensive set. At best, this gives a team only about 50% or less of the time on the shot clock in which to run their offense. To think about that another way, if basketball and lacrosse were to have a similar balance between transition time and time in the offensive set it would be like playing basketball with a 10-12 second shot clock or lacrosse with a 30-40 second shot clock.

“I can’t tell you how many times I would see both teams moving down the pool at half-speed on the counterattack. No wonder we are trying to shorten the course to twenty-five meters. A slow counter is really boring”

—Dante Dettamanti (Interview Part 1)

That discussion of time brings us back to the concept of space. If traversing a 30 meter course in water polo eats up half the shot clock, what would that look like in the other sports mentioned? In basketball you would extend the field of play to 250 feet or more baseline to baseline while keeping the 24 second shot clock in order to have a similar relationship between transition time and the shot clock. In lacrosse, the field of play would be extended to 800 feet or more with an 80 second clock to maintain a proportional relationship between the shot clock and the field of play similar to water polo. Whether thinking about this concept in terms of shortening the shot clock or lengthening the field of play in either of those sports, the incongruity of the shot clock in water polo with the medium in which the game is played and the size of the field of play becomes a little more obvious. So instead, let’s take the time and space in water polo and see if it can’t be brought more in line with the example of the other shot clock sports examined.

Using the numbers derived above, it can be postulated that transition time should make up about 20-25% of the shot clock which leaves about 75-80% of the shot clock remaining for a team to run its offense. In a 30 meter water polo course, a 60 second shot clock would translate to a 25% transition time and 75% time spent in the offense. However, the 30 meter course is perhaps part of the issue here. Frankly, that just seems to be too much space when it is considered that the majority of players are within 9 meters of the opposing goal when on offense. There is a huge amount of relatively unused space in the middle of the pool.

So, assume a course of 25 meters and the speed above would suggest a transition time of about 12 seconds. One could then derive a shot clock of perhaps 45 seconds so that roughly 26% of the clock would represent the time in transition and the remaining 74% would be free for set offense. 25 meters has been experimented with and rejected in international play, but this analysis suggests that without an adjustment in the shot clock as well there will not be a notable positive impact on play.

Even more extreme, a 20 meter course (shorter even than the 25 yard pool that is standard in the United States) that a player could traverse in roughly 10 seconds would still suggest a shot clock of 35-40 seconds instead of 30 seconds in order to maintain the balance between transition and set offense that the other sports suggest is ideal.

“The game played at 20 meters length, provides instant action on any turnover similar to basketball, and once in the frontcourt the players can freely move and make many more spectacular plays. Beautiful plays that you see in current water polo maybe 2-3 times a game occur regularly”

Wolf Wigo (Rules Rule #1)

I am fairly certain that many within water polo will see the numbers above and immediately balk. What I suggest will be labeled as moving backwards; it will be said that the sport is trying to speed up, not slow down. However, there is nothing inherent in a longer shot clock that precludes or discourages fast play. In fact, shortening the course as I’ve suggested may allow for a greater incidence of fast breaks simply because it will be easier for players to sprint the distance required to counterattack and passes can be delivered quicker and more accurately over the shorter distance. The shorter course would also provide more opportunities for the goalie to be involved in the offensive attack as the new rules allow and make flying substitutions quicker and more meaningful. Moreover, the development of offenses like the 7 seconds or less Suns in the NBA suggests that the restraint of the shot clock isn’t the hindrance to the pace of play that is feared.

I will go even further, however. I propose that it is both the 30 second shot clock and the 30 meter course combined–both the elements of time and space in the game–that are the major contributor to the lack of offensive variety and innovation in the sport of water polo. As mentioned earlier, coaching is a conservative profession and the trend in that profession has been to push to optimize the efficiency of organized team play. In water polo, this has translated to an emphasis on drawing exclusions and penalties at the center position. Due to the length of the course and shortage of time, offense in water polo invariably involves passing the ball around in a desperate attempt to find an entry to the center. Movement and driving is kept to a minimum because coaches do not want to commit an offensive player to a drive with the worry that time will expire or an offensive foul will be called and leave the team at a disadvantage defensively.

Likewise, the lack of time to develop offense generally means that a team can only mount a single or possibly two phases of attack in any given possession; lacking the ability to reset the offense and run multiple phases of attack results in coaches prioritizing the center entry to get the most bang for their offensive buck. Given more time in which to work, teams would be free to explore more varied and creative offensive concepts and formations. If stalling was still a concern, the incorporation of a time frame in which the ball must pass into the offensive half of the pool could be added. As is the case with the current shot clock, added time would not prevent or preclude players from taking quality open opportunities as they become available in the offense; however, the added time would allow for more variety and creativity in how teams attempt to create these opportunities. The hope would be that this increased time would open the game up to more interesting and varied tactical approaches including offenses based on motion, picking or other concepts. More time gives more opportunities for tactical play to develop and the example of other sports demonstrates that longer doesn't mean slower. Notably, the motion game that many in the sport pine for and that encourages the dynamic, skillful finishes many love had its heyday during the era of longer shot clocks.

“[T]he way the game used to be played, front court offense was exciting to play and watch. Now frontcourt offense is just a means to get to an end (a 6/5)”

Wolf Wigo (Rules Rule #1)

World Aquatics (formerly FINA) justified the current 30 second shot clock by pointing to its increasing pace of play; however, this rationale seems to misunderstand that there is a point of diminishing returns between pace of play and tactical or offensive variation. The current lack of tactical variations in the game of water polo and many of the complaints leveled against it—that the game is boring or the possessions repetitive—can be directly connected to the issues of time and space created by the current shot clock and size of the course. Altering these two elements would not be a panacea for all of the issues the sport faces, but re-examining these elements in light of the difficulty of the medium in which the game is played and the example provided by other sports with similar rules could potentially move the game forward and expand the way in which it is played. Much like the story of the 24 second clock in basketball, these decisions could and should be made foremost in the interests of providing a better experience for the spectators by increasing the variety of tactical approaches and allowing for greater opportunities for players to create skillful and exciting finishes.

Perhaps, after reading all of the above (and if you have I am thankful) some readers may be unconvinced that increasing the shot clock and/or decreasing the length of the course would have a positive impact on the tactics and spectator experience of water polo. If so, I would leave those readers with one final thought: This entire analysis has focused on elite male players in water polo and their speed and ability. It can be recognized that women even at the elite level are not, on average, as fast as an elite man (time standards for swimming can illustrate this if there is doubt). Moreover, age group athletes of both genders can not hope to match the swimming speed of elite adult men. So, why is water polo unique among sports with a shot clock in providing no allowance in the shot clock and almost no variation in course size across age and gender? Maybe the shot clock and course length for international competitions do not need to be changed, but we as a sport should at least discuss why we expect age group athletes to compete within the same parameters as elite adults and what impact this has on their development and enjoyment of the sport.

Sources and Further Reading

Rules Rule #1: Why We Need to Rewrite the Rules of Water Polo!

Rules Rule #2: The Future of Water Polo and All Sports Comparison

Interview with Dante Dettamanti Part 1

If you made it this far, please consider sharing and subscribing so you wont miss any more opportunities to keep thinking water polo!

Really enjoyed your take on things and appreciate the comparisons to other sports and how it translates to water polo! Thanks Breck!

Hi Breck. I hope life is treating you well. Enjoyable article - I like your polosiphising! You know I always agreed with Dante that motion is what makes a game exciting, and as you mention way back in the day, the game was much more counter-attack based and encouraged lots of movement.